Ontario Mining Legacy Project

The History of Mining in Ontario

The Ontario Mining Association celebrated its 100 year anniversary in 2020. As part of the #ThisIsMining campaign, a legacy project was created to explore some of the rich history of mining in Ontario. This legacy project was on display at the historic Design Exchange (the original Toronto Stock Exchange building) in downtown Toronto for the OMA 100th anniversary gala in May 2022, and now lives online - please enjoy this brief history of Ontario Mining!

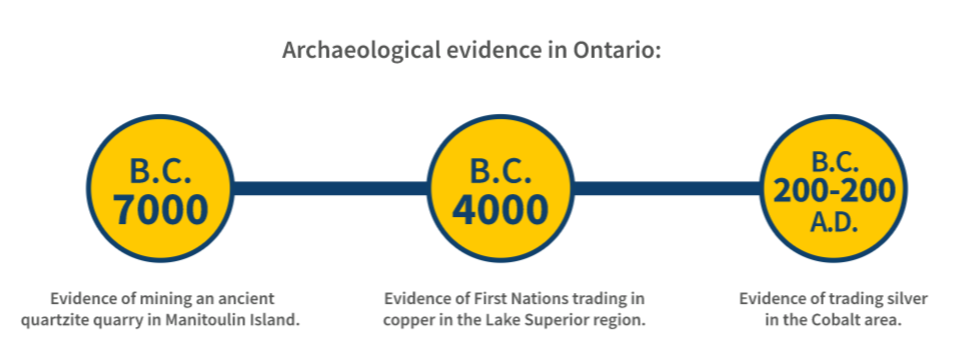

Earliest Evidence of Mining in Ontario

The first Aboriginal inhabitants of the Americas arrived approximately 40,000 years ago, most likely from Asia during a late Pleistocene interglacial period, but also possibly by boat via the Pacific (across the Bering Strait) and Atlantic oceans. The First Nations that settled on the continent utilized and traded various minerals to produce tools, weapons and decorative objects, including pebbles and cobbles, flint, chert, pipestone, native copper, gold, silver and turquoise.

Spear point or knife, Laurentian Archaic, Ottawa Valley, 6100 years ago. Native Copper. Canadian Museum of History, BkGg-11:1049

It is important to acknowledge the established, long-standing presence of Ontario’s Indigenous peoples, on whose traditional territories our industry developed. Much of our early exploration, development and mining operations were done without proper consent or involvement, and these existing communities often did not benefit from these resources as they should have.

These First Nations – including the Anishinabewaki, Cree, Algonquin, Mississauga, Haudenosaunee, Métis and others – were likely the first to have uncovered and made use of many of these riches from the Earth, but accounts of their early explorations were lost to early settler historians.

Our knowledge gaps in Indigenous pre-history and our treatment of Indigenous people in the colonization of what is now Ontario deserves a more complete exploration than what is presented here. These important perspectives are currently missing from our story.

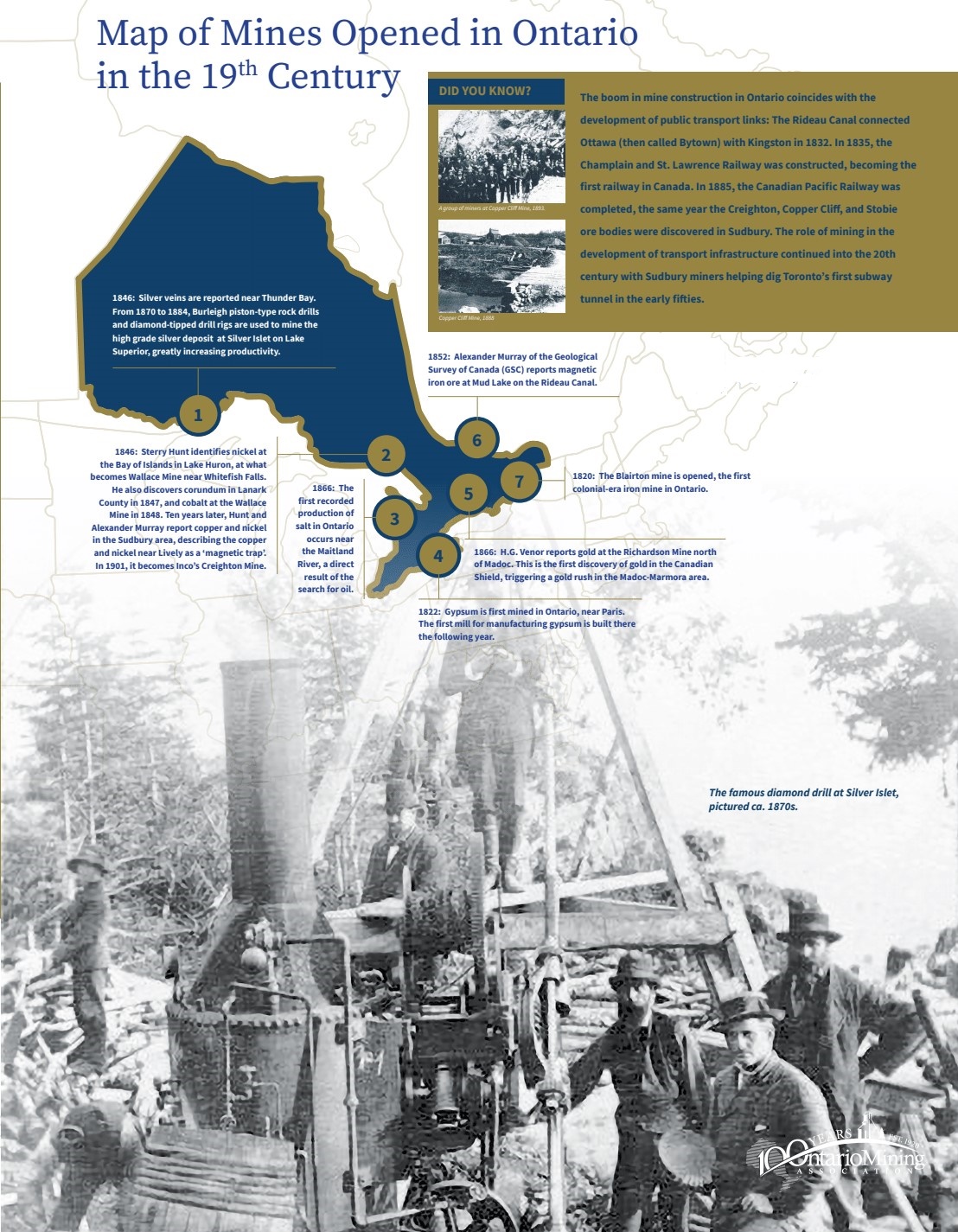

Colonial Canada: Exploration in the "New World"

For centuries, Canadian land was occupied and re-occupied by colonists arriving from Europe. Eager to take economic advantage of the resource-rich Canadian landscape, explorers pursued a wide range of mining and trading opportunities. By the mid-19th century, support from the newly established British colonial government had helped the mining industry in Canada grow at an unprecedented rate.

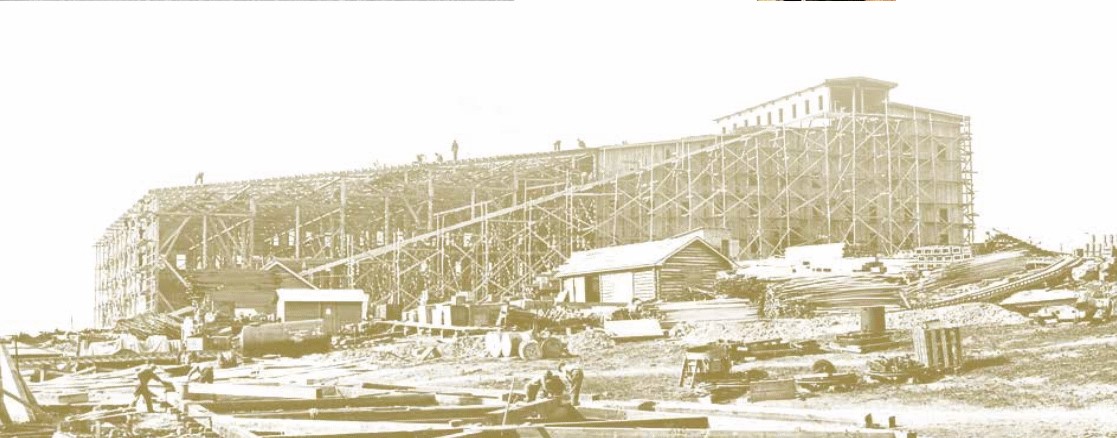

The Creation of Mining Institutions Across Ontario

As the map of active mines in Ontario grew, formal institutions related to the mining industry flourished. The establishment of educational facilities and market structures that could enable the sustainable growth of the mining industry were central to the economic and scientific success of Ontario as a whole.

In 1842, the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) was founded in Montreal. In 1902, Ontario appointed its first provincial geologist, Willet Green Miller. He was later credited with being one of the first people to recognize the importance of silver discoveries at Cobalt, as well as developing a method to identify diamonds, emeralds, corundum and energy using X-rays.

In the 19th century, studies in geology and mining engineering were introduced in several Ontario colleges and universities. The School of Mining and Agriculture in Kingston – the first department specifically dedicated to mining studies – was established by the government of Ontario on May 27, 1893, and soon incorporated into Queen’s University. In 1912, the Haileybury School of Mines was established, to meet the demand for technically trained miners in the silver camps around Cobalt.

Science Building: Kingston businessman John Carruthers donated $10,000 toward the construction of a new science building, Carruthers Hall. It was an early necessary step in establishing applied science and engineering programs at Queen's. For Carruthers it was an investment in keeping Queen's in Kingston.

Ontario was the first Canadian province to enact legislation that would serve as a model for other jurisdictions. In 1891, the Ontario Bureau of Mines was established, becoming the Ontario Department of Mines in 1919. In 1906, the provincial government enacted the Ontario Mines Act to delineate simple guidelines for securing interests in mining claims and to ensure the certainty and security of titles. It allowed for the simple and speedy settlement of disputes concerning ownership claims through the appointment of a mining commissioner, and abolished all crown royalties on production.

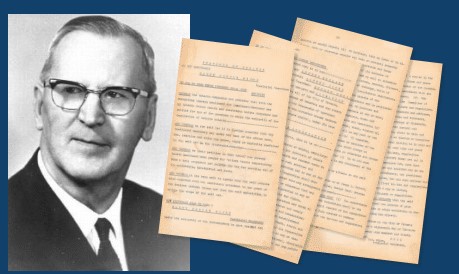

On February 20, 1920, the Ontario Mining Association was incorporated, by the incumbent Provincial Secretary the Hon. Harry Corwin Nixon. Its charter purpose was to promote and foster the business of mining, to support and aid in the establishment of any conveniences deemed beneficial to its members, and to pursue educational and charitable objectives. The very first Directors undersigned in the official document are Frank Culver, Alfred James Young, George Cecil Bateman, Alexander Fasken, and finally, Arthur Dorland Miles, who is elected as the first President of the corporation and later Chairman of the Executive Committee.

On February 20, 1920, the Ontario Mining Association was incorporated, by the incumbent Provincial Secretary the Hon. Harry Corwin Nixon. Its charter purpose was to promote and foster the business of mining, to support and aid in the establishment of any conveniences deemed beneficial to its members, and to pursue educational and charitable objectives. The very first Directors undersigned in the official document are Frank Culver, Alfred James Young, George Cecil Bateman, Alexander Fasken, and finally, Arthur Dorland Miles, who is elected as the first President of the corporation and later Chairman of the Executive Committee.

In 1878, the Toronto Stock Exchange was formally incorporated. In 1908, the Standard Stock and Mining Exchange was created specifically to deal with public interest in junior mining issues following the great Cobalt Silver Boom, which played a vital role in contributing to Toronto’s emergence as a national and international financial centre.

In 1989, the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame had its first induction ceremony, presided over by chairman Maurice (Mort) Brown, then-publisher of The Northern Miner.

In 1989, the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame had its first induction ceremony, presided over by chairman Maurice (Mort) Brown, then-publisher of The Northern Miner.

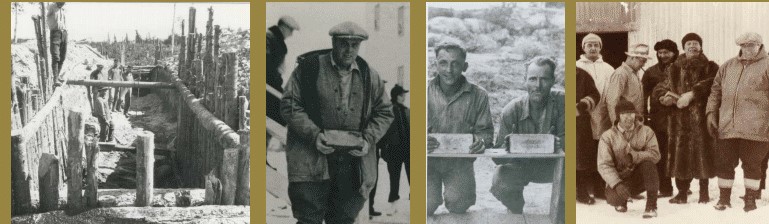

Prospecting in Ontario

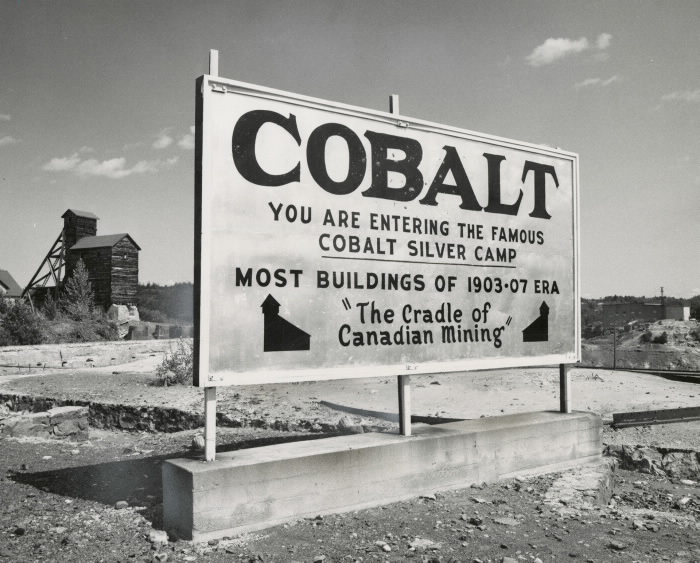

THE DISCOVERY OF SILVER IN COBALT, IN THREE PARTS

In August 1903, railroad subcontractors J.H. McKinley and E.F. Darragh find silver bearing float in Cobalt Lake. Assayers at McGill University report native silver at an astonishing 4000 ounces of silver to the ton.

In August 1903, railroad subcontractors J.H. McKinley and E.F. Darragh find silver bearing float in Cobalt Lake. Assayers at McGill University report native silver at an astonishing 4000 ounces of silver to the ton.- A few weeks later, silver is discovered at the south end of Cobalt Lake when Timiskaming and Northern Ontario railway blacksmith Fred LaRose throws a hammer at a passing fox. The hammer misses the fox, but overturns a rock, revealing silver. The LaRose Mine would go on to produce 26 million ounces of silver.

- A third discovery by Tom Herbery eventually becomes the “Big Nip” mine – the largest producer in the camp – generating a staggering 91 million ounces of silver by the time it closes in 1950.

The Cobalt discoveries made news headlines throughout North America, feeding stock market frenzy. Spreading to New York in 1906, police were forced to break up crowds frantically trying to buy silver mining shares on Wall Street. The silver boom is credited with making the Toronto stock exchange and banking community a global mine financing powerhouse. Silver production in Cobalt reached its peak in 1911, with over 31 million ounces produced that year alone.

HOW AIR TRAVEL TRANSFORMED THE PROSPECTING LANDSCAPE

Prospecting with aircraft in Ontario began with the use of a sea plane to ferry geologists, prospectors and supplies to the Belcher Islands in Hudson’s Bay in 1920. In 1928, Northern Aerial Minerals Exploration (N.A.M.E.) was formed, with the support of financier John Hammell. Air travel greatly reduced the length of any prospecting mission, increasing the efficiency of mineral exploration in remote regions.

Prospecting with aircraft in Ontario began with the use of a sea plane to ferry geologists, prospectors and supplies to the Belcher Islands in Hudson’s Bay in 1920. In 1928, Northern Aerial Minerals Exploration (N.A.M.E.) was formed, with the support of financier John Hammell. Air travel greatly reduced the length of any prospecting mission, increasing the efficiency of mineral exploration in remote regions.

In 1935 and 1937, the airport at Howey Bay, on Red Lake, was recognized as the busiest in the world. As a hub for aircraft transporting both freight and passengers, it saw more take-offs and landings than any other airport – averaging one every 15 minutes.

AIR PROSPECTING DEVELOPMENTS

1920: The first instance of air prospecting in northern Ontario is the use of a large sea plane to ferry geologists, prospectors and supplies to the Belcher Islands, in Hudson’s Bay; the use of the plane reduces the trip to Belcher Islands from the usual three to four weeks by canoe or boat to about four to five hours.

1928: The Northern Aerial Minerals Exploration (N.A.M.E.) is formed, with the support of financier John Hammell. N.A.M.E. operates 10 aircraft from 34 bases located across Canada’s northern regions to service the activities of 200 prospectors. Out of N.A.M.E. grow the companies that form Canadian Airlines, Canada’s second largest airline at the time of its merger with Air Canada in 2001, illustrating the vital role of the mining industry in the healthy functioning of our modern system of everyday conveniences.

1928: In September, the editor of The Northern Miner (Richard Pearce) accompanies Dominion Explorers (in collaboration with Western Canada Airways) on the first plane crossing of the Barren Lands lying between Hudson Bay and the Mackenzie River basin, lands said to have never been traversed by man before. The trip, intended to survey the conditions under which prospecting parties would be working, is the most ambitious of its kind made in Canada at the time, taking 40 flying hours spread over 12 days, and covering 3,900 miles.

1936: Howey Bay, at the heart of Red Lake, is recognized as the busiest airport in the world in both 1935 and 1937. It is a hub for aircrafts transporting both freight and passengers, with more flights landing and taking off per hour than any other (at 15 minute intervals.)

The late 1950s and early 1960s sees a scaling up of the mining industry, major productivity gains and leaps in the sophistication of exploration technology. In 1957, North Ranking nickel mine in the Northwest Territories, the so-called first truly Arctic mine in North America, begins production.

1955: Production of rock salt begins in Windsor as the Ojibway salt mine is opened. High-grade iron ore is derived from pyrrhotite tailings at Inco’s new plant at Copper Cliff.

The ascendancy of airborne geophysical surveying in the late 1960s brings a flurry of mineral discoveries and mine developments in some of the world’s most inhospitable places. In this era we see mines built in some of Canada’s most forbidding northern locales.

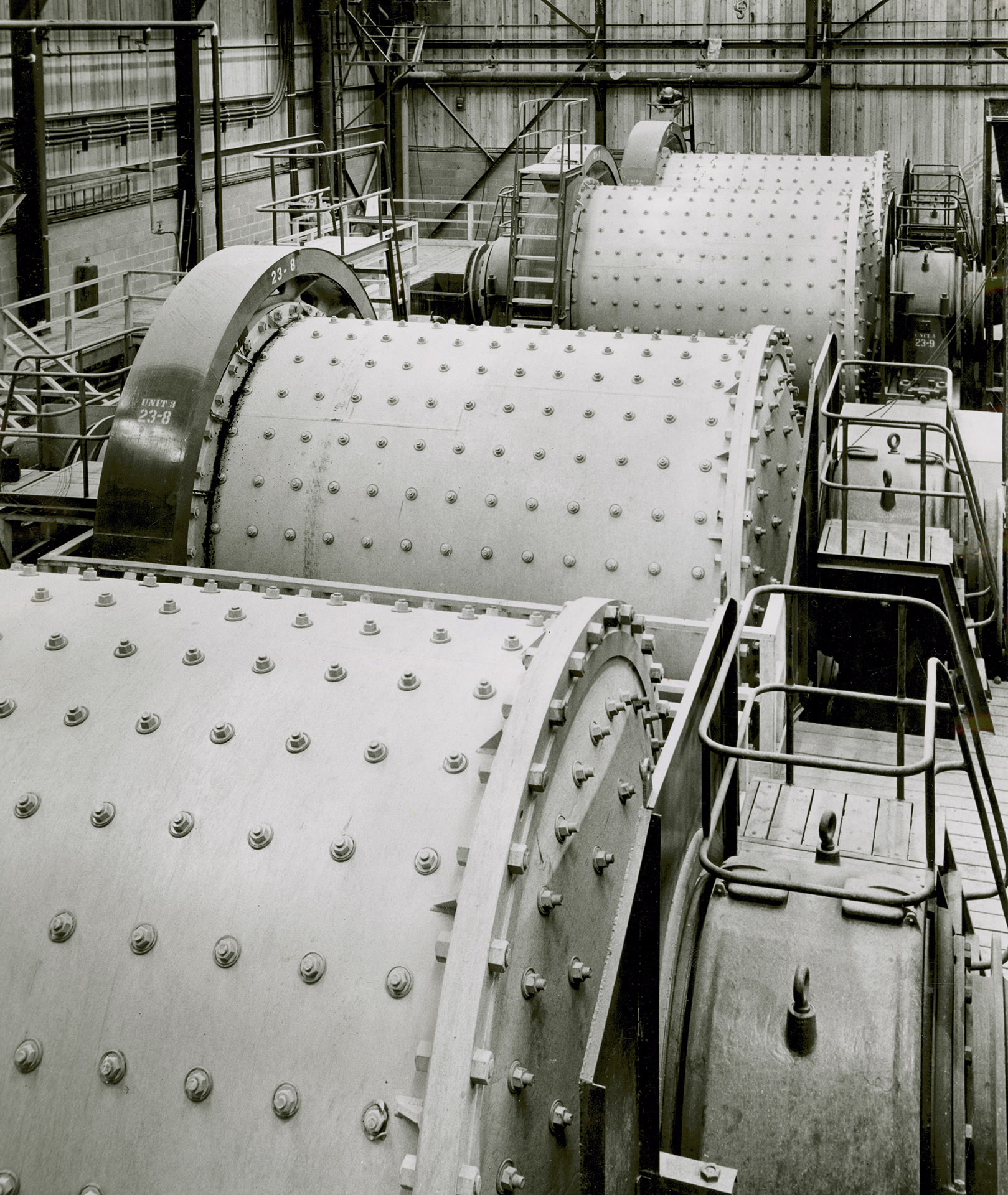

Metallurgy and Innovation in New Mining Technologies in the 20th Century

In the 20th century, mining productivity in Ontario improved significantly. Innovative companies and individuals developed new standards and best practices in extraction and refining, bringing greater prosperity to the industry.

In the 20th century, mining productivity in Ontario improved significantly. Innovative companies and individuals developed new standards and best practices in extraction and refining, bringing greater prosperity to the industry.

At the forefront of metallurgical innovations, the International Nickel Company (Inco) created Monel Nickel in 1906, a nickel-copper alloy with high tensile strength and resistance to corrosion. The alloy came to be used in a variety of goods, from aircraft like the ‘60s-era North American X-15 rocket plane to the RotoSound bass guitar strings used by Iron Maiden, The Who, and Sting. Inco’s metallurgical research and development continued throughout the 20th century, creating high-tech alloys for turbine engines, nuclear generators and other industrial machinery that ushered in the jet age.

The Inco team would also go on to develop the matte flotation method of copper-nickel separation, flash smelting of copper for better sulphur recovery, and the carbonyl and anode processes of refining nickel, all major improvements in nickel metallurgy.

In the early 1940s, Markham chemist Lloyd Pidgeon developed the Pidgeon process – in which finely powdered calcined dolomite and ferrosilicon are mixed to produce high purity magnesium metal. The process played a vital role in the war effort, providing manufacturers with a strong, light-weight material for aircraft construction. It is still used today to produce most of the world’s highest purity magnesium metal, as well as calcium, barium and strontium.

Archibald's Achievements

From 1934 to 1940, chemist Frederick Archibald of Seaforth works with Queen’s University professor G.J. MacKay to invent the MacKay Process for treating arsenical ores to extract gold. Archibald, later named Chief Metallurgist of Falconbridge, is a prolific metallurgist who makes significant contributions to many chemical processes in the mining industry:

- fluid-bed roasting and electric furnace smelting technology,

- techniques applied in Sudbury mines to wring more nickel from ores there,

- and the Hydride Process, a method of extracting uranium that plays a crucial role in the Second World War for the production of uranium metal from Canadian uranium oxides, and a key component in the Manhattan Project.

In 1973, chemical engineer Bert Wasmund invented a cooling technology for smelting furnaces to more cost-effectively extract valuable products from lower grade ores. He later improved the technology to capture emissions from smelters, an important contribution to the sulphur dioxide abatement program in Sudbury in the 1970s and 1980s. Replacing outdated blast furnaces with a new process using fluid-bed roasters and electric furnaces dramatically improved air quality and helped reduce acid rain.

In 1989, Wasmund and his Mississauga-based engineering company Hatch Ltd., created an electric smelting furnace which revolutionized the platinum industry, tripling daily production and reducing energy requirements by 25%.

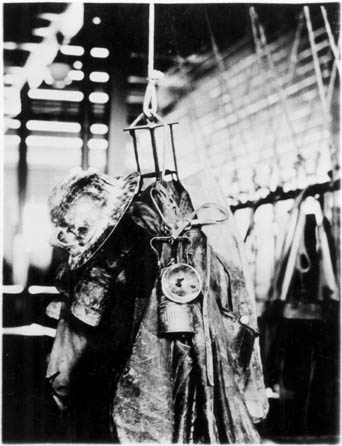

Landmark Developments in Health and Safety in the 20th Century

.jpg)

Today, Ontario’s mining industry is considered one of the safest in the world, meeting the industry objective of zero-fatalities in 2016 and 2018. But the journey to “zero harm” in the Ontario mining industry spanned the entire 20th century, and was marked by milestones that demonstrate a commitment to accountability, and a prioritization of health and safety objectives in Ontario’s policy-making.

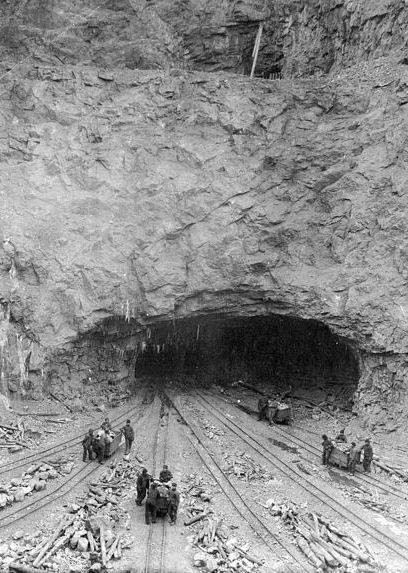

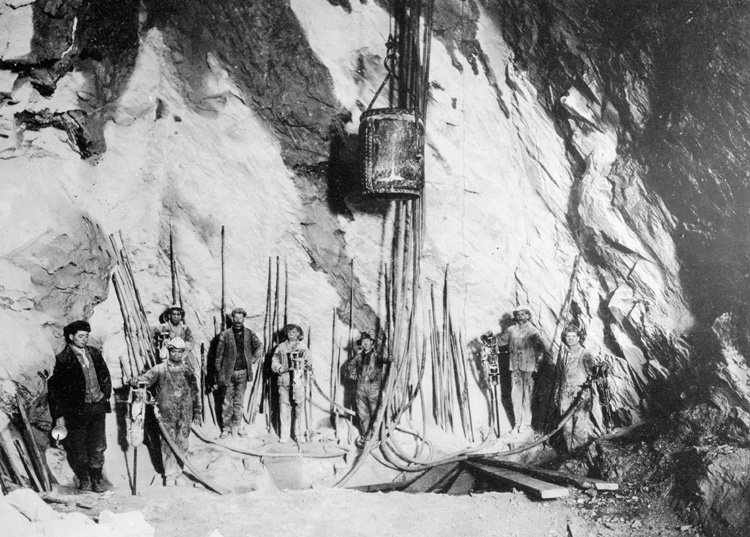

The first legislation passed to tackle mining safety issues was the Mining Operations Act of 1890, which established rules for ventilation, blasting, manholes, lifting devices, shafts, signals, brakes, machinery and boilers. But it was not until 1928 that Ontario’s journey to becoming a world leader in mine safety would truly be galvanized.

The first legislation passed to tackle mining safety issues was the Mining Operations Act of 1890, which established rules for ventilation, blasting, manholes, lifting devices, shafts, signals, brakes, machinery and boilers. But it was not until 1928 that Ontario’s journey to becoming a world leader in mine safety would truly be galvanized.

After a tragic fire at the Timmins Hollinger Consolidated Gold Mine, a Royal Commission outlined several recommendations to improve safety practices and equipment in mines. Most significant was the creation of the first Ontario Mine Rescue in Timmins in 1929. The Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy began recognizing the mine with the lowest annual compensable accident record in 1941. And in 1950, Ontario initiated an annual Mine Rescue Competition, encouraging mine rescue teams to remain well trained and ready to respond to emergencies.

Several further commissions would go on to redefine mine safety in Ontario became the first Canadian province to pass a legislative framework around workplace injury, with the 1915 Workmen’s Compensation Act. The Act enforced a system of collective liability for accidents, as well as automatic payment and means of rehabilitation for resulting injuries. In 1978, the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) further expanded upon the legal definition of workers’ rights. Ontario. In 1974, miners in Elliot Lake initiated a three-week strike to protest the rising incidence of silicosis and lung cancer in mines which had supplied yellowcake to the U.S. military at the apex of the Cold War, – and were now producing most of the Western world’s uranium. In 1976, Premier Bill Davis convened a royal commission to investigate health and safety in mines, generating more than 100 recommendations, including the Internal Responsibility System. In 1982, the Burkett Commission report on mine safety led to the creation of a governance model for incident investigations. Three years later, the Stevenson Commission on mine safety produced improved training and communication protocols to deal with rockbursts, rock falls, wall collapses and other non-fire emergencies.

Several further commissions would go on to redefine mine safety in Ontario became the first Canadian province to pass a legislative framework around workplace injury, with the 1915 Workmen’s Compensation Act. The Act enforced a system of collective liability for accidents, as well as automatic payment and means of rehabilitation for resulting injuries. In 1978, the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) further expanded upon the legal definition of workers’ rights. Ontario. In 1974, miners in Elliot Lake initiated a three-week strike to protest the rising incidence of silicosis and lung cancer in mines which had supplied yellowcake to the U.S. military at the apex of the Cold War, – and were now producing most of the Western world’s uranium. In 1976, Premier Bill Davis convened a royal commission to investigate health and safety in mines, generating more than 100 recommendations, including the Internal Responsibility System. In 1982, the Burkett Commission report on mine safety led to the creation of a governance model for incident investigations. Three years later, the Stevenson Commission on mine safety produced improved training and communication protocols to deal with rockbursts, rock falls, wall collapses and other non-fire emergencies.

Learn more about the future of zero harm in mining.

An Industry in Solidarity With the People: Ontario Mining’s Contributions to the War Effort

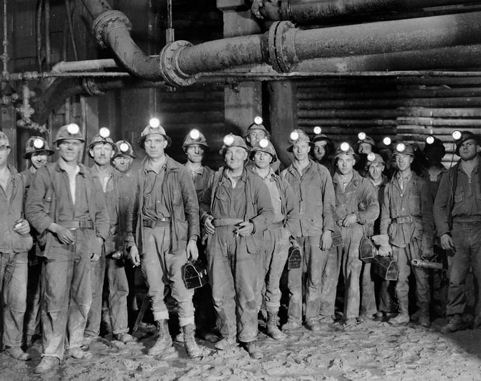

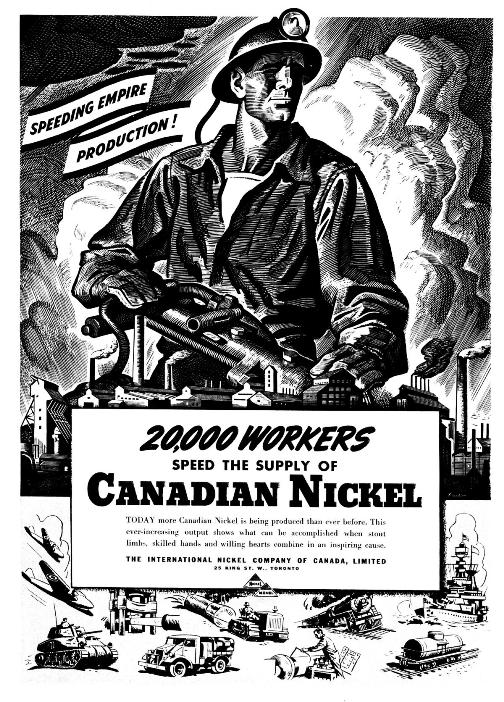

By World War II, mining was no longer the fledging industry it was during World War I, and quickly became essential to the Allied victory over the Axis powers of Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan.

Gold Mining Continues

While many countries deemed gold mining to be a non-essential activity, the Canadian government encouraged gold production as a means of paying for the country’s war expenditures. In 1942, Prime Minister Mackenzie King took a firm stand on the conservation of war materials necessitating the curtailing of non-war industries. Plans to release men from work to support the war effort should, he said, “have due regard to the nature of the industry and its continuance as a soundly functioning industry in the post-war period.” Despite the loss of men to voluntary enlistment, Ontario gold mines increased production from 3,086,000 ounces in 1939 to 3,262,000 in 1940, and a nearly consistent 3,194,000 ounces in 1941.

While many countries deemed gold mining to be a non-essential activity, the Canadian government encouraged gold production as a means of paying for the country’s war expenditures. In 1942, Prime Minister Mackenzie King took a firm stand on the conservation of war materials necessitating the curtailing of non-war industries. Plans to release men from work to support the war effort should, he said, “have due regard to the nature of the industry and its continuance as a soundly functioning industry in the post-war period.” Despite the loss of men to voluntary enlistment, Ontario gold mines increased production from 3,086,000 ounces in 1939 to 3,262,000 in 1940, and a nearly consistent 3,194,000 ounces in 1941.

Strategic Minerals

Nickel and copper were essential to the war effort. Nickel is a highly strategic metal, used in all forms of military hardware, including tanks, battleships, planes and ordinance. Inco delivered 1.5 billion pounds of nickel, 1.75 billion pounds of copper and more than 1.8 million ounces of platinum metals to Allied countries during World War II – an astounding 95 percent of all Allied demand for nickel. The company produced the same amount of ore during the war years as in its entire 54 preceding years, all while profits declined.

A Collective Sacrifice

Despite annual earnings of Ontario base metal mines declining over the course of the war – due to fixed pricing, rising costs and short supplies of equipment, materials and manpower – no mine operator objected to the price control measures imposed to aid the war effort of Canada and her allies. In a show of solidarity, when Falconbridge’s nickel-copper refinery in Kristiansand, Norway was seized by invading German troops in 1940, Inco offered to store Falconbridge matte in its refinery on a toll basis for the duration of the year.

1938: Steep Rock Iron Mines is incorporated at Steep Rock Lake near Atikokan, Ontario. Upon drilling there, three extensive, high-grade deposits are discovered. Their cultivation presents a formidable challenge, resulting in one of Canada’s greatest engineering feats: diverting the river and draining and dredging the lake to allow access to the iron ore. Steep Rock becomes a priority project during WWII, due to its strategic importance for the Allied war effort as a source of hematite ore (the first shipping of which occurs in 1944).

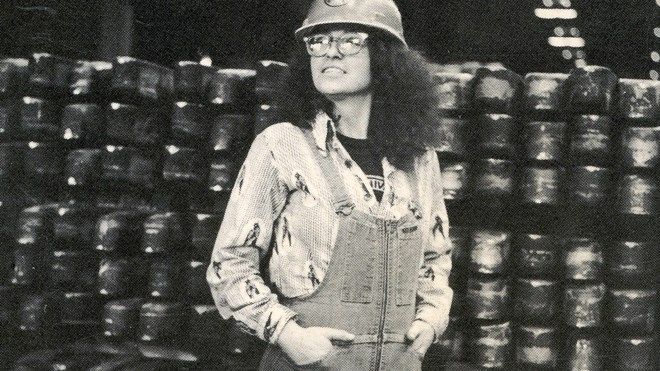

Women in Mining in Ontario

The 1884 Ontario Factories Act prohibited women from working in mines. In 1942, however, with labour shortages brought on by the Second World War, a federal order under the War Measures Act allowed women to be employed, but only in surface operations. Over 1400 women filled a variety of roles – in the crushing mills, rock house, and refineries – but were not allowed underground, and were never given official titles.

The 1884 Ontario Factories Act prohibited women from working in mines. In 1942, however, with labour shortages brought on by the Second World War, a federal order under the War Measures Act allowed women to be employed, but only in surface operations. Over 1400 women filled a variety of roles – in the crushing mills, rock house, and refineries – but were not allowed underground, and were never given official titles.

While the restriction was reinstated at the end of the war, these workers were a shining example to those who fought to eventually repeal of the ban on women working in mines.

Inco Vice-President R.L. Beattie commented in a 1946 speech that “an Allied victory would have been impossible had the women not stepped into the employment breach … when labour was critically short, and the need for our products on the battlefronts steadily increasing.”

In May 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth became the first members of the British Royal family to visit nickel operations in Sudbury, Ontario. It was the first time a reigning British monarch had ever visited Canada, and the Queen became the first woman to go underground in the Frood Mine. During the war, about 40% of Allied nickel came from the mine’s open pit alone.

In May 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth became the first members of the British Royal family to visit nickel operations in Sudbury, Ontario. It was the first time a reigning British monarch had ever visited Canada, and the Queen became the first woman to go underground in the Frood Mine. During the war, about 40% of Allied nickel came from the mine’s open pit alone.

Cynthia Cameron, a 19-year-old student at the Haileybury School of Mines, became Ontario’s first certified female mine rescuer in 1978. The year also marked the start of the lifting of the legislative ban on women working underground in Ontario.

Cathy Mulroy was one of the first women hired in a non-traditional role at Inco after the Second World War, working in the anode department casting molten metal in the copper refinery. A tireless advocate for women’s rights in male-dominated industries, she was injured in a work-related accident in 1986. She returned to Inco as the first woman to teach First Aid and CPR, and the first female safety surface instructor.

Cathy Mulroy was one of the first women hired in a non-traditional role at Inco after the Second World War, working in the anode department casting molten metal in the copper refinery. A tireless advocate for women’s rights in male-dominated industries, she was injured in a work-related accident in 1986. She returned to Inco as the first woman to teach First Aid and CPR, and the first female safety surface instructor.

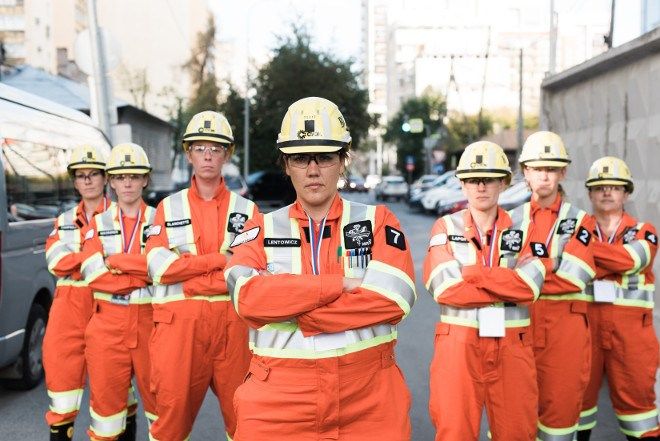

The Diamonds in the Rough were the first all-female Canadian team to compete at an international mine rescue competition. At their debut at the 2018 IMRC in Russia (where it is still illegal for women to work in underground mines), they won the People’s Choice Award.

A Prosperous Industry: The Discovery of Gold in Ontario

THE PORCUPINE GOLD RUSH

Gold was first discovered near Porcupine in 1908. The rapidly spreading news led to a frenzy of exploration in the area, known as the Porcupine Gold Rush. By 2001, 67 million troy ounces of gold had been mined, making it by far the largest gold rush in terms of actual gold produced.

Key discoveries in the Gold Rush

- Exploration efforts fan out from Cobalt. Harry Preston slips on a rock, and by ripping the moss cover, uncovers a rich gold vein in 1909 (the “Golden Staircase”) which comes to be known as the Porcupine Mining District

- Jack Wilson, a member of his crew, founds the Dome Mine (today owned by Newmont, the Dome is Canada’s longest running gold mine, and has produced more than 67 million ounces of gold since beginning production in 1910)

- Benny Hollinger discovers the Hollinger Mine

- Alexander Olifant (alias Sandy McIntyre) goes on to stake McIntyre Mine (which, in its operating years from 1912 to 1988, manages to produce a total of 10.8 million ounces of gold)

- News of the discovery stimulates a rush to the area. Brothers Noah and Henry Timmins incorporate Hollinger Gold Mines to develop claims in the area in 1910, and the town of Timmins is established in 1912

The Red Lake Rushes

In 1925, brothers Lorne and Ray Howey discovered gold under the roots of an upturned tree near Red Lake, spurring the last great series of North American gold rushes. Over 3000 people converged on this tiny isolated outpost in January 1926, travelling by dog team or by foot over frozen rivers and lakes, along burned-out roads and over fallen trees.

In 1925, brothers Lorne and Ray Howey discovered gold under the roots of an upturned tree near Red Lake, spurring the last great series of North American gold rushes. Over 3000 people converged on this tiny isolated outpost in January 1926, travelling by dog team or by foot over frozen rivers and lakes, along burned-out roads and over fallen trees.

The difficult journey helped introduce aviation to the exploration business, with John Hammell’s newly-formed Patricia Airways airlifting supplies to the prospect area with seven chartered bush planes. This was only the first in a series of gold rushes in the Red Lake area.

Second Red Lake Gold Rush

After several months of exploration, George Campbell strikes gold in Red Lake. On October 4, 1944, Campbell, in the process of developing a new trench, finds samples with fine visible gold; the assay results from the samples range from nine to five ounces of gold per tonne. News of the discovery quickly spreads throughout the mining community in Red Lake, and after World War II ends, thousands of prospectors flood to the area. This second Red Lake gold rush only lasts a single year, but has a great impact on the mining industry there. Over the course of 1946, over 5,000 men and women come to Red Lake in search of gold. Prospectors make an estimated 20,000 claims, and 150 new companies are created. The 1946 gold rush results in numerous new producing mines in the existing Red Lake mining camp.

After several months of exploration, George Campbell strikes gold in Red Lake. On October 4, 1944, Campbell, in the process of developing a new trench, finds samples with fine visible gold; the assay results from the samples range from nine to five ounces of gold per tonne. News of the discovery quickly spreads throughout the mining community in Red Lake, and after World War II ends, thousands of prospectors flood to the area. This second Red Lake gold rush only lasts a single year, but has a great impact on the mining industry there. Over the course of 1946, over 5,000 men and women come to Red Lake in search of gold. Prospectors make an estimated 20,000 claims, and 150 new companies are created. The 1946 gold rush results in numerous new producing mines in the existing Red Lake mining camp.

The Great Depression

While much of the world’s economy suffered under the Great Depression, Canada’s emerging gold camps prospered from the Great Gold Boom that followed the rise of gold prices from September 1931 onwards. By 1930, Canada was the world’s second-largest gold producer, with Ontario producing 1.7 million of the nation’s 2.1 million total ounces.

In the 1980s, the Hemlo deposit near Marathon, Ontario became one of the country’s richest gold camps – revitalizing the Canadian gold mining industry. A furious staking rush saw Hemlo become Canada’s top gold production centre and largest underground gold mine. It was also the site of one of the most important claim jumping battles in Canadian mining history, with Teck-backed junior miner Corona Corp. ultimately awarded ownership of the Williams mine over Lac Minerals by the Supreme Court of Canada in 1989.

In 1983, Peter Munk founded Barrick Gold. With the help of geologist Brian Meikle and mining engineers Bob Smith and Alan Hill (later president of Barrick), Barrick Gold was rapidly transformed from a fledgling gold company into the world’s pre-eminent gold producer, with mines and projects on five continents and the world’s largest gold reserves.

This is Mining

In 2020, the OMA launched #ThisIsMining, a public campaign to celebrate the association’s centennial. To commemorate its 100th anniversary, we asked the people of Ontario to take a fresh look at mining – to discover everything the industry has become, and all it has to offer. The campaign provides an overview of the industry in unexpected ways – through individual stories that celebrate diversity and inclusion, the thrill of an exciting and adventurous career, the transformational effects of innovation and digitization, the drive to protect our environment and take climate action, and the legacy of community building in Ontario. The lives and legacies of the following individuals paved the way for a campaign like #ThisIsMining.

John Bickell is one of few people listed in both the Hockey Hall of Fame and the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame. Born in 1884, Bickell became president of McIntyre-Porcupine Mines in 1919, and served as the OMA’s chairman in 1923 and 1924. He was an early shareholder of the Toronto St. Pat’s hockey team, becoming the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1927. After his death in 1951, the J.P. Bickell Foundation was established, and has since distributed more than $85 million. Half of the Foundation’s income goes to Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children.

Ontario-native Kathleen Creighton Starr Rice formed the Rice Island Nickel Company in central Manitoba in 1928. Born in 1882, she rose to fame for her exploration endeavours, which saw her covering 800km on foot, dog sled and canoe to find zinc, vanadium, gold and nickel deposits throughout Canada. The Canadian Mining Hall of Fame describes her as an “innovative dog trainer” with a strong respect for First Nations groups, who often worked with her on her journeys. She was also responsible for introducing borax crystals to North America, used today in metallurgical processes as a flux (an agent used to clean or purify chemical substances.)

Incorporated by brothers Ed and Bill Cochenour and their partner Dan Willans in Red Lake in 1936, Cochenour-Willans Gold Mines had an enormous impact on the development of the surrounding area during its producing years from 1939 to 1971. It supported the community by providing key amenities, establishing a trust fund to support recreation and healthcare projects, and even bring Christmas presents to underprivileged children. Today, the work is continued by Newmont Goldcorp in collaboration with the Wabauskang and Lac Seul First Nations. They work together to invest in economic development, local infrastructure, recreational facilities, educational and cultural youth programs, and the Red Lake Medical Clinic.

Barrick Gold founder Peter Munk is remembered as one of Canada’s most prolific philanthropists, donating nearly $300 million of his mine-made wealth to various causes and institutions. The Peter Munk Cardiac Centre at the Toronto General Hospital was established in 1997 with a $75 million donation. An additional $100 million contribution in 2017 remains the largest single gift ever made to a Canadian hospital. As Canada’s premier cardiac centre, the facility treats over 160,000 patients a year. Munk gave the University of Toronto $47 million to create the Munk School of Global Affairs, and in 2008 founded The Munk Debates, Canada’s most important public policy debate series.

#STEM

Few might expect to find that SNOLAB, Canada’s leading physics research laboratory, is located in a mine – two kilometres underground in Sudbury’s Creighton Mine. The grand opening in 1988 was attended by Stephen Hawking, who visited again in 2012. In 2015, the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory’s director of research Art McDonald was co-awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for that experiment’s contribution to the discovery of neutrino oscillation.

The OMA’s Educational Initiatives Go Way Back…

1948: The Ontario Mining Association sponsored an “Essays on Mining” contest for Ontario high school students, an idea circulated as early as July 1922 by committee members. The contest, which encouraged students to examine the importance of the mining industry to the province, was won by ten students in 1949 and another ten students in 1950. They were awarded two-day long trips to Kirkland Lake and Sudbury respectively, touring the underground and surface operations of local mines as well as visiting points of interest in the area.

1962: The OMA directors approved a recommendation by the Committee on Publications of Reports to distribute a Northern Miner booklet titled “Mining Explained in Simple Terms” to schools in Ontario; 1700 copies were made available to all secondary schools and to a select group of primary schools in the province.

2009-2016: OMA ran a video contest for Ontario students called So You Think You Know Mining, receiving almost 1,000 entries from across the province and giving out over $272,000 in prizes to students, teachers and schools.

2017: OMA partnered with Moses Znaimer's ideacity conference to co-curate a mining-themed session. The session, held on June, 15, 2017, was part of a series of talks that looked at technological disruption and innovation.

2017-2018: the OMA ran the MINED Open Innovation Challenge, which offered Ontario university students a chance to solve a real-life mining challenge, win $15,000+ and gain invaluable exposure to industry leaders.

2010 - present: Mining Matters, the Canadian Ecology Centre, the Canadian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy and the OMA have been delivering Mineral Resource and Mining Education Tours (watch the 10th anniversary video). The tours are Earth science and mineral resource professional learning programs available to Formal and Informal Educators, as well as Mineral Resource Development Advisors, from across Canada.

A Green Industry: The Environmental Movement in the Mining Industry

In the latter half of the 20th century, the mining industry in Ontario took great strides to address its impact on the environment. In 1972, the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change was created (followed by the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines in 1985), which aimed to promote environmentally-conscious attitudes to monitoring mining projects. The OMA Environment Committee was also formed that year, cementing the industry’s drive to introduce transparent and effective sustainability initiatives.

Although a global environmental movement was slow to develop, the mining industry was quicker than most. As early as the 1960s, Inco engineers had embarked on a mission to reduce sulphur dioxide emissions at the company’s Sudbury operations – a process that also resulted in improved recoveries from the ore and more useful commercial products. In 1966, Agnico constructed a 1000 tonne-per-day reclamation plant to recover silver contained in the tailings that had been deposited in Cobalt lake, nicknamed the ‘million dollar lake’ by the local community. Over three summers, the company recovered more than 600,000 ounces of silver from over 300,000 tonnes of waste material.

By the 1990s, the global environmental movement was finally well underway. In Ontario, this corresponded to the introduction of rehabilitation programs in environments affected by negative externalities of mining, and in 1990, mine closure plans and reclamation became part of the Ontario Mining Act. For example, under the direction of Walter Curlook, Inco completed a $600 million dollar sulphur dioxide abatement program in Sudbury in 1993. At the time of completion, it was deemed to be the largest environmental protection project ever undertaken in the mining industry.

By the 21st century, Ontario had become a leader in mining reclamation and rehabilitation efforts. In 2007, together with the Canadian Land Reclamation Association (CLRA), and with the support of Vale (formerly Inco), the OMA launched the Tom Peters Memorial Mine Reclamation Award. The purpose of the award is to encourage the pursuit of excellence in mine reclamation and to recognize and promote, to the mining industry and environmental community at large, outstanding achievement in the practice of mine reclamation in Ontario.

In 2008, the OMA announced a partnership with the Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines to rehabilitate mine tailings at the Kam Kotia Mine near Timmins. The footprint of the former copper-zinc mine, which had been out of operation since the 1970s, has now been reduced from 500 to 200 hectares of covered, sealed and controlled tailings – such that the environment can now “sustain vegetation, control erosion, reduce contamination and support wildlife,” according to the ministry.

In 2019, the Vale Living with Lakes Centre launched the Community Restoration of Acid Damaged Lakes (CRADL) with the support of Vale, Laurentian University and the Ontario ministries of Environment, Conservation and Parks, and Natural Resources and Forestry. This project aims to shed light on the status of fish populations and food webs in acid damaged lakes, and subsequent efforts to reintroduce lake trout to the area have already surpassed expectations.

Sudbury is now a beacon of hope, an example to the world that learning from the past can inspire us to do better. Experience the story of Sudbury’s environmental achievements through the lens of two photographers OMA commissioned to document the city's re-greening process.

The greatest opportunity for the mining industry today in its effort to embrace a greener future is the technological advancement which has emerged out of the last few decades. Mining companies are increasingly designing their operations to use battery-powered equipment. Kirkland Lake Gold was the first to introduce battery electric vehicles in their operations and in 2020, commissioned the world’s first 50 t battery electric truck for use underground. Glencore is currently developing the Onaping Depth site to operate an all-electric mining vehicle fleet, while Newmont installed 38 pieces of electric equipment at its Borden mine near Chapleau, leading to a significant reduction in GHG output and enhanced employee safety with the reduction of diesel particulate emissions. Companies are further embracing automation, tele-remote operations and digitization. Goldcorp’s Red Lake Gold Mines implemented tele-remote operation of scoops from the surface in 2015, adding an underground loci (locomotive engine used to transfer ore and waste rock material) in 2017. Barrick Gold partnered with Cisco to implement a digital transformation of their operations. Self-driving vehicles and sensors are now making mines safer for employees, while data and analytics are helping refine processes. The collective efforts of OMA members to introduce innovative technologies highlight Ontario mining’s role in setting industry standards to promote better environmental and safety practices, while ensuring cost-effectiveness and productivity.

A Few Ontario Mining Superlatives: A History of Outcompeting the World

1896: Operations begin at the Canada Talc Mine located in Madoc. Mining operations continued until 2010 making this one of only three mines on the planet which have been in steady operation for more than one hundred years.

1896: Operations begin at the Canada Talc Mine located in Madoc. Mining operations continued until 2010 making this one of only three mines on the planet which have been in steady operation for more than one hundred years.

1903: The world's richest vein of silver was found at Cobalt, Ontario.

1912: The Hollinger, McIntyre and Dome mine start producing gold. These became three of the largest gold mines ever found in North America with 47 million ounces of gold produced having a total value of US$59 billion in today's dollars. The Dome mine was in production for 109 years.

1912: The Hollinger, McIntyre and Dome mine start producing gold. These became three of the largest gold mines ever found in North America with 47 million ounces of gold produced having a total value of US$59 billion in today's dollars. The Dome mine was in production for 109 years.

1930: The first Ontario Mine Rescue Manual is produced and distributed to mine rescue teams.

1930: The first Ontario Mine Rescue Manual is produced and distributed to mine rescue teams.

1934: Mining companies contribute 29% off all dividends paid by Canadian corporations, according to OMA records, highlighting the critical economic importance of the industry.

1934: Mining companies contribute 29% off all dividends paid by Canadian corporations, according to OMA records, highlighting the critical economic importance of the industry.

1954: Drilling at Denison Mines in Elliot Lake uncovers the largest uranium deposit in the world at the time. The Denison mine would become the largest underground uranium mine in North America.

1954: Drilling at Denison Mines in Elliot Lake uncovers the largest uranium deposit in the world at the time. The Denison mine would become the largest underground uranium mine in North America.

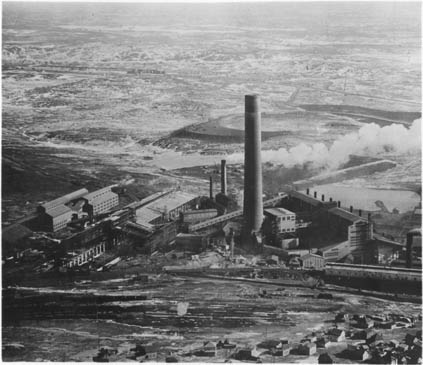

1954: The world’s tallest smelter chimney, 637 feet above ground level, is erected in Sudbury to serve the iron ore recovery plant of Inco.

1954: The world’s tallest smelter chimney, 637 feet above ground level, is erected in Sudbury to serve the iron ore recovery plant of Inco.

1959: Salt mining operations begin at the Goderich salt mine. Tunnelling 1,800 feet under Lake Huron, it becomes the largest underground salt mine in the world – as deep as the CN Tower in Toronto is tall.

1959: Salt mining operations begin at the Goderich salt mine. Tunnelling 1,800 feet under Lake Huron, it becomes the largest underground salt mine in the world – as deep as the CN Tower in Toronto is tall.

1964: After half a decade of development, the Kidd-Creek copper-zinc-silver sulphide deposit is mapped north of Timmins, using geophysical, geological and diamond drill methods. Kidd-Creek is still in production today – considered the deepest base-metal mine in the world.

1964: After half a decade of development, the Kidd-Creek copper-zinc-silver sulphide deposit is mapped north of Timmins, using geophysical, geological and diamond drill methods. Kidd-Creek is still in production today – considered the deepest base-metal mine in the world.

1964: Sudbury opens The Big Nickel park, with its nine-metre replica of a 1951 Canadian nickel becoming the world’s largest coin. The 1951 design was chosen to mark the bicentennial of the chemical isolation of nickel by Swedish chemist Baron Axel Frederic Cronstedt.

1964: Sudbury opens The Big Nickel park, with its nine-metre replica of a 1951 Canadian nickel becoming the world’s largest coin. The 1951 design was chosen to mark the bicentennial of the chemical isolation of nickel by Swedish chemist Baron Axel Frederic Cronstedt.

1969: Redpath completes the sinking of the 7,138 foot No. 9 shaft at Inco’s 69-year-old Creighton Mine – the deepest continuous single-lift mine shaft in the Western Hemisphere at the time.

1969: Redpath completes the sinking of the 7,138 foot No. 9 shaft at Inco’s 69-year-old Creighton Mine – the deepest continuous single-lift mine shaft in the Western Hemisphere at the time.

1972: Inco’s 1250-foot “Super Stack” is completed at Copper Cliff – the highest in the world until 1987, and second only to the CN Tower as the tallest structure in Canada.

1972: Inco’s 1250-foot “Super Stack” is completed at Copper Cliff – the highest in the world until 1987, and second only to the CN Tower as the tallest structure in Canada.

-Low-Res.jpg) 2007: The Ring of Fire camp is revealed to contain the fourth largest reserve of chromite in the world, as well as nickel, copper, platinum group elements, gold, zinc, and vanadium, estimated to be worth at least $60 billion.

2007: The Ring of Fire camp is revealed to contain the fourth largest reserve of chromite in the world, as well as nickel, copper, platinum group elements, gold, zinc, and vanadium, estimated to be worth at least $60 billion.

2013: Geoscientists from the University of Toronto discover a pocket of water approximately 1.5 billion years old at Kidd Creek mine, nearly 2.4 km underground. Its formation predates the existence of multicellular life. In 2016, researchers find water roughly 2 billion years old in the mine’s boreholes nearly 3 km deep. The ancient water is found to contain chemical traces left behind by a single-celled organism that once lived there.

2013: Geoscientists from the University of Toronto discover a pocket of water approximately 1.5 billion years old at Kidd Creek mine, nearly 2.4 km underground. Its formation predates the existence of multicellular life. In 2016, researchers find water roughly 2 billion years old in the mine’s boreholes nearly 3 km deep. The ancient water is found to contain chemical traces left behind by a single-celled organism that once lived there.

TODAY: The past 100 years have been fruitful for the mining industry in Ontario and its success has driven the Ontario economy forward. It has also enabled progressive change, with an important focus on being responsible and sustainable miners. Where we are today – leaders in responsible mining – will energize our next 100 years. And, in turn, we are energizing the next 100 years of progress in Ontario. Our vision is to be the safest, cleanest, most technologically advanced mining jurisdiction – supplying the world with the responsibly sourced minerals and metals people need to make modern life and innovation possible.